OUR BLOG

Aleksandar Raković: Third Way Through the Cold War

Post-war Yugoslavia and its diplomacy successfully avoided the trap of bloc alignment and, together with countries from all over the world, helped establish a completely new principle in global politics.

The Third Way.

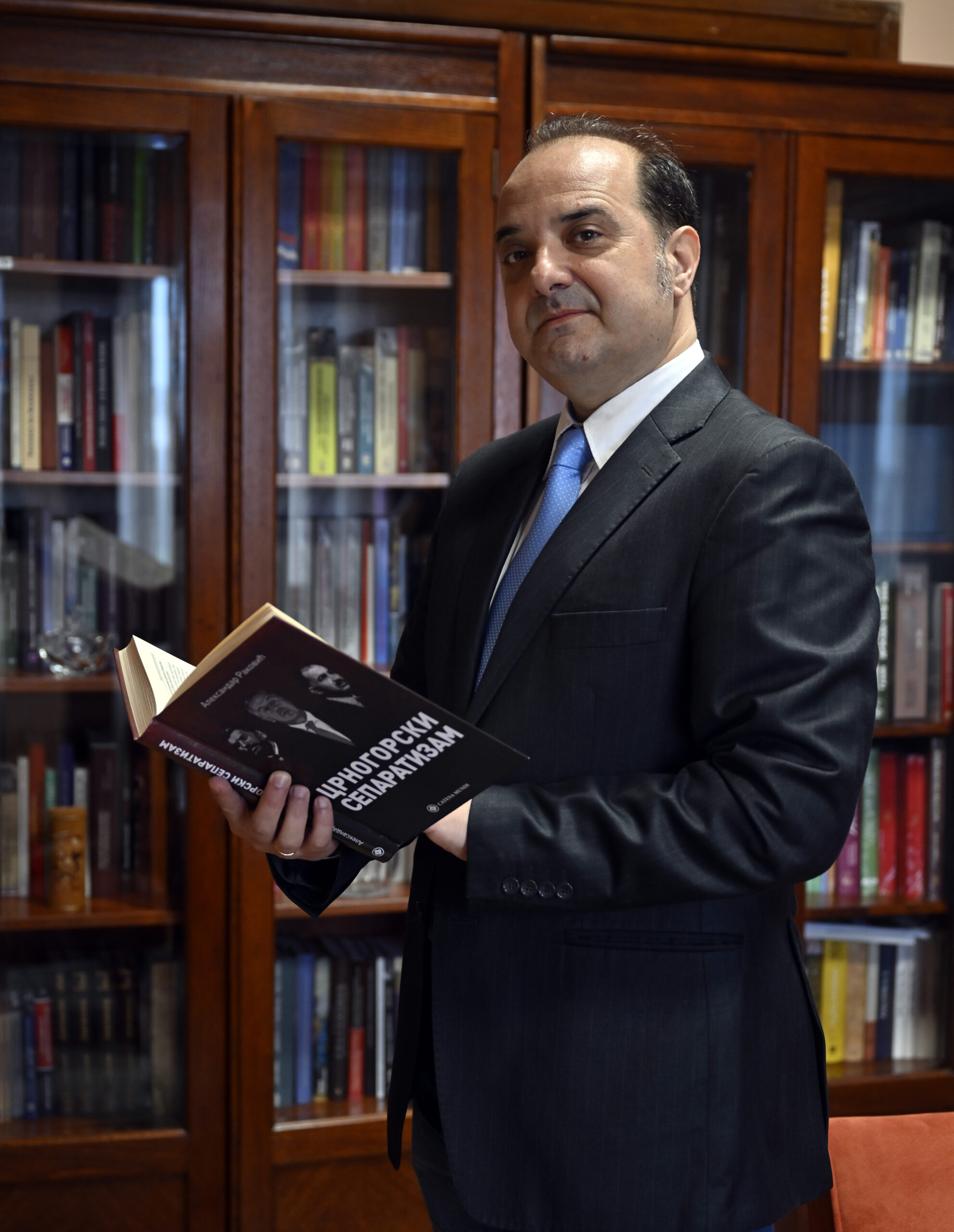

This phrase best summarizes the course Yugoslavia took after World War II, which allowed Belgrade to occupy a key place in global politics for decades. By refusing to align with the dominant blocs led by the Soviet Union and the United States, and by striving for an independent policy, the idea of non-alignment was born. This introduced a brand-new principle into international relations during the Cold War. The movement—authentic in many ways and born amid the sharpest Cold War tensions—was a quiet but significant diplomatic victory that accelerated the development of our country, enhanced its reputation in the world, and whose legacy is still recognized today.Historian Aleksandar Raković, senior research associate at the Institute for Contemporary History of Serbia, highlights the legal and state continuity between the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and Socialist Yugoslavia, while also emphasizing the many benefits achieved through skillful diplomatic balancing between East and West. Broadly speaking, the Kingdom of Serbia was a key actor in Balkan politics, the Kingdom of SHS/Yugoslavia in European and Mediterranean politics, and Socialist Yugoslavia in global politics.

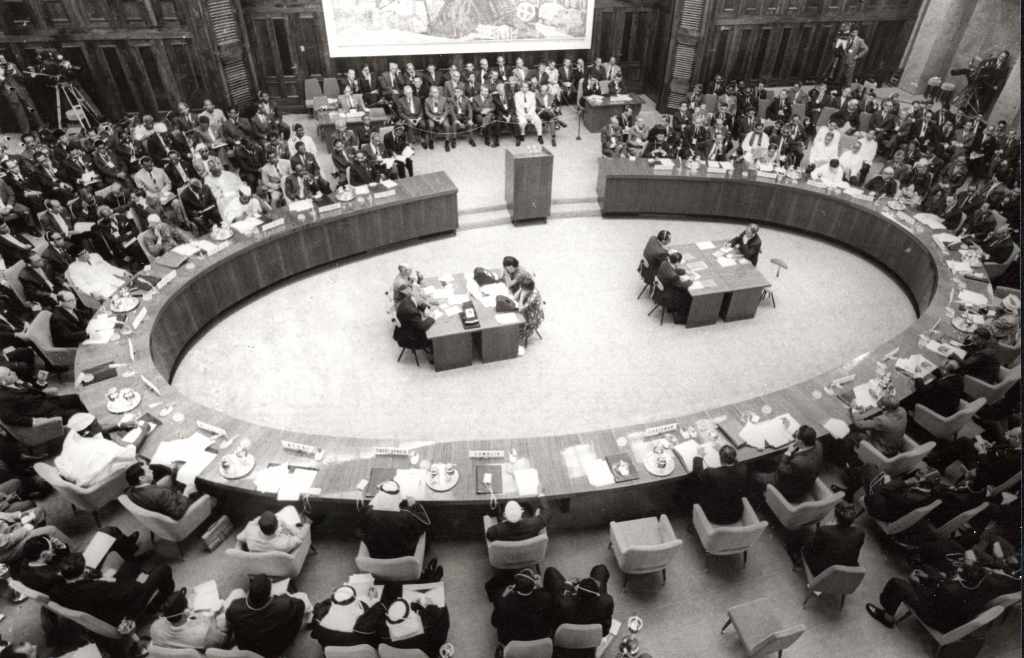

Прва конференција Покрета несврстаних, одржана 1961. године у Београду / Фото: Музеј Југославије

“The split with the Cominform over differing visions of socialism in 1948 led to a political conflict between Yugoslavia and Moscow, but it also marked a major foreign policy shift for Belgrade. After assessing the situation, the United Kingdom and the United States concluded that the conflict was not staged and that Yugoslavia could be used to build ties with the West. Yugoslavia’s turn was first evident in the economy. From the mid-1950s onward, despite its socialist structure, the economic system was increasingly tied to the West. The policy of belt-tightening was abandoned, and the state encouraged consumer culture, supported in part by foreign loans,” explains Raković.

The conflict with the USSR ended with Stalin’s death in 1953. Although Belgrade and Moscow restored relations in the following years, Yugoslavia never returned to the socialist bloc. Tito was aware of the Asian-African Conference held in Bandung in April 1955, whose decisions closely resembled the principles of Yugoslavia’s foreign policy. Accordingly, after Tito’s visits to India and Burma in 1954/55 and his meeting with Egyptian President Nasser on the return journey, the foundations of Yugoslavia’s “Third Way” policy were laid. It was a policy of decolonization, peaceful coexistence, anti-segregation—meaning neutrality and non-alignment—and later, the formal Non-Aligned Movement.

Since 1961, the movement included countries of vastly different systems: communist and socialist states, monarchies, parliamentary democracies, and even Orthodox theocracies like Cyprus, led by the “Castro of the Mediterranean,” Archbishop Makarios.

“The Non-Aligned Movement was an effective way for Yugoslavia to avoid full dependence on either of the opposing blocs. Yugoslavia’s economy could not compete with the West, but it was very capable of achieving economic breakthroughs in Third World countries. As a result, Belgrade became a global political and cultural hub. Additionally, the non-alignment policy brought Yugoslavia allies, securing it voting power in the UN General Assembly. The Non-Aligned Movement became a force that both NATO and the Warsaw Pact leaders had to reckon with,” our interviewee emphasizes.

You may read the complete interview in the latest edition of our Dipos Magazine.

2018

2018