OUR BLOG

Cyrillic Script Is the Memory of Serbian People

The Cyrillic script is an ancient script that was created back in the times of the Old Slavonic language. Throughout history, it spread among all Orthodox Slavs, and has been their main script since the 12th century. Evеn though the Cyrillic script is one of two official scripts in Serbia, it is much more than just the official script for the Serbian people. It is a symbol of cultural identity, history, and linguistic distinctiveness. It was created in the 9th century and has shaped and nurtured language, literature, and spirituality ever since. It was used to write the first laws, poems, gospels and charters, and later books, textbooks, magazines, and scientific papers. According to academician Matija Bećković, ‘the Cyrillic script is the spiritual DNA of the people that use it’.

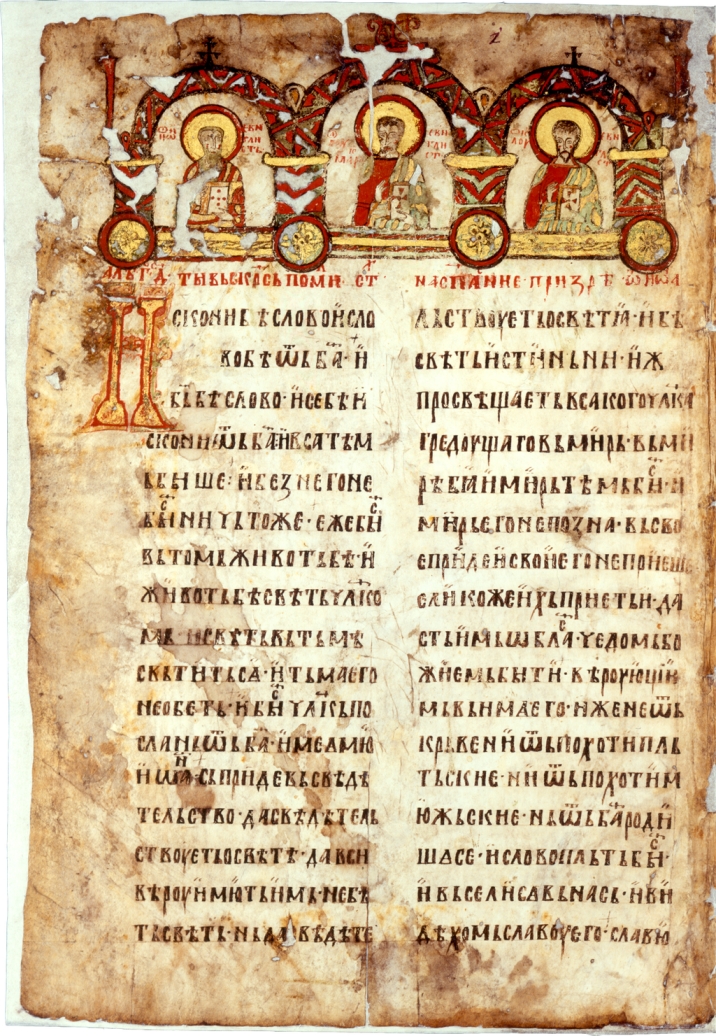

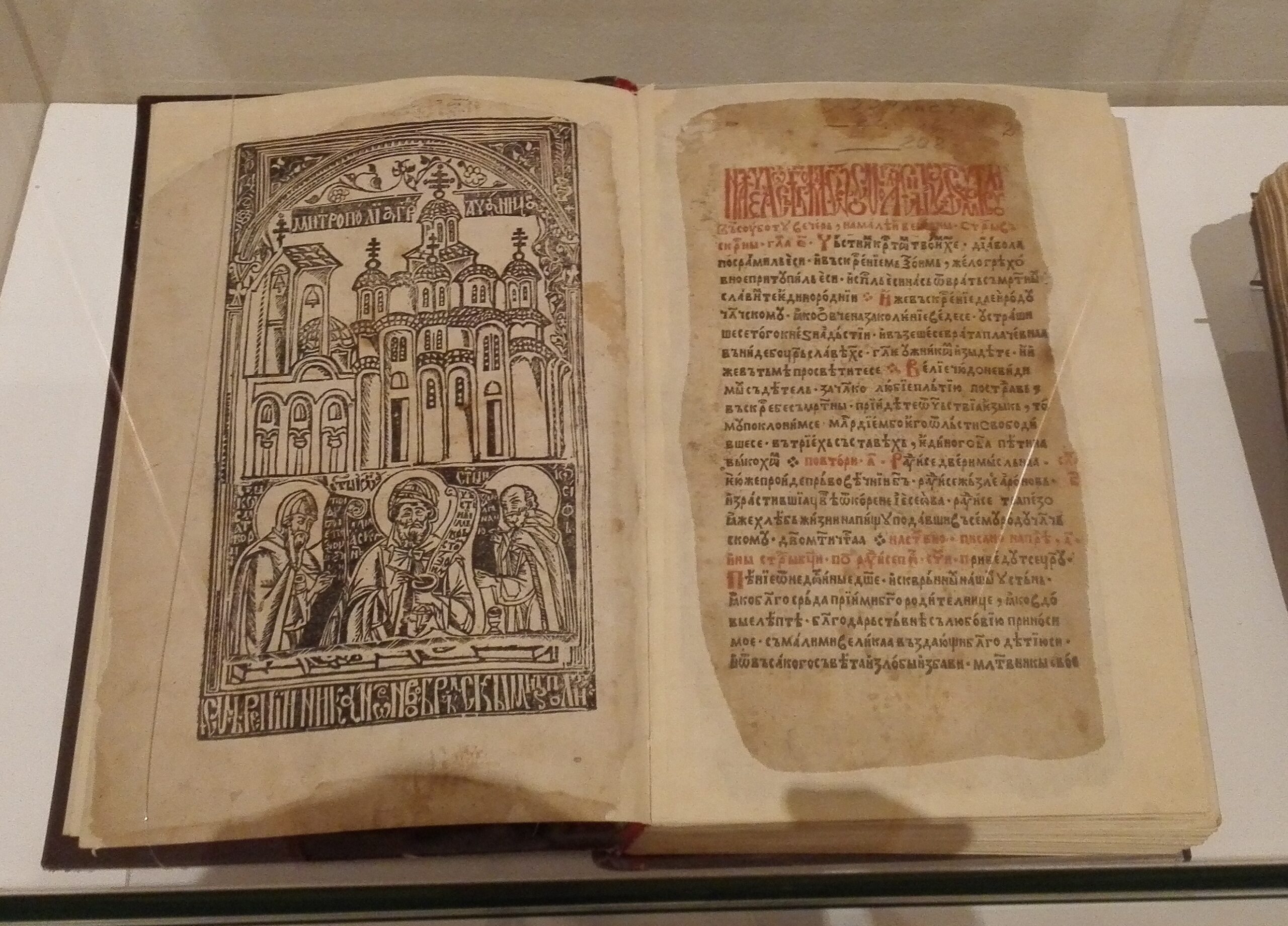

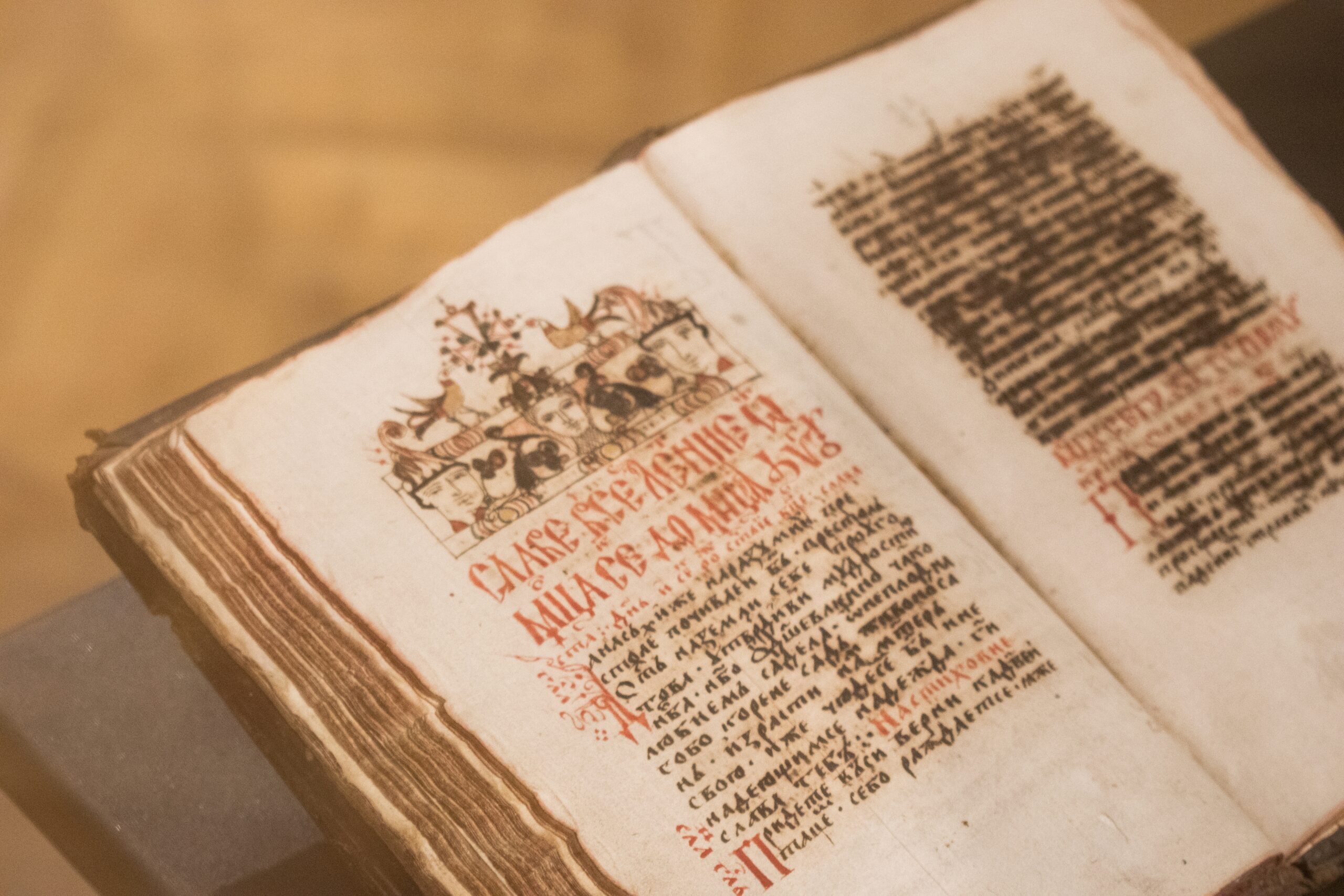

Poetically speaking, the Cyrillic script is a link between what we used to be and what we are now. It is no accident that Petar Petrović Njegoš’s masterpiece Mountain Wreath was printed in Cyrillic or that it was used in 1494 in the Crnojević printing house in Cetinje for the first book in the Cyrillic script of the South Slavs – the Octoechos. The Cyrillic script was also used for the Code of Emperor Dušan and for the inscriptions carved into the stones of old Serbian monasteries such as Hilandar, Dečani, and Studenica.

The Cyrillic script is protected by the Serbian Constitution, which affirms its specific importance for Serbian history and culture. According to the Constitution, the official language in Serbia is Serbian, and the official script is Cyrillic. This provision makes the Cyrillic script not only a means of communication but a symbol of statehood and cultural continuity.

Its usage is also regulated by the Law on the Official Use of Language and Script. The Cyrillic script is mandatory in the documents of state bodies, public institutions, and the media funded from the state budget. The Cyrillic script has also been recognised by the Law on Culture as part of Serbia’s cultural heritage. According to Professor Sreta Tanasić, PhD, scientific advisor in the Serbian Language Institute of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, ‘the Cyrillic script is the only Serbian national script and a key element of cultural identity of the Serbian people. The vast majority of the writings in Serbian cultural heritage, including the most important documents, such as the Miroslav Gospel, were written with the Cyrillic script. It is the essential part of our cultural heritage that we should be proud of.’

The famous Serbian director Emir Kusturica defined the organic connection between the Cyrillic script and the endurance of the Serbian people even more succinctly. ‘The Cyrillic script represents our memory. It is the graphical image of the Serbian people’, Kusturica said. However, the graphical image of the Serbian people did not come easily or overnight. Today’s Cyrillic script compiles the hard work of generations of learned individuals since the Middle Ages. Its roots go back to the endeavours of Saints Cyril and Methodius, who created the Glagolitic alphabet in the 9th century as the first script adapted to Slavic phonemes. As a tribute to the two brothers from Thessaloniki, 24 May was chosen as the Day of Slavic Literacy and Culture. Their equally important students, Clement and Naum, composed a new script – the Cyrillic, which unified.

However, there was a problem in the territory of medieval Serbia – the Old Slavonic language, the first literary language of all Slavs, was never the spoken language of Serbs, but was only the liturgical language. This is how the Serbian recension of Old Slavonic came to be – the Serbian Slavonic language, which had more vernacular words. This language was not a spoken language either, even though it was the language of prayers chanted in church.

Parallel with the Ottoman occupation, the Church invited Russian teachers to Serbia who brought with them the Russian Slavonic language, which is still used in Orthodox churches of Balkan Slavs, with minor differences. However, this language was also difficult to understand, so elements of the vernacular Serbian language were again introduced to writing and speech. That is how a combination of languages know as Slavonic-Serbian was created and remained in use as the official literary language until the late 19th century.

The story of Serbian Cyrillic is, however, inseparable from Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, who advocated for the use of the vernacular in literature. He is not only seen as the creator, but as the biggest proponent of the principle ‘write as you speak and read as it is written’. Karadžić relied on the efforts of philologist Sava Mrkalj, who advocated the reform of script and orthography based on the principle ‘one sound – one letter’, and created a codified system of written communication which became one of the pillars of our identity. It connects epochs, the land and the language and is an international brand of Serbia. This is how Karadžić’s script became a symbol of Serbia.

In his reform, Karadžić removed the redundant letters from Russian Cyrillic, kept 24 Old Slavonic symbols, adopted the letter J from the Latin script and introduced five new ones – Ћ, Ђ, Џ, Њ, and Љ.

In a contest for the most beautiful letter of the Serbian Cyrillic – once known as ‘Vukovica’ after its creator – there is a high probability that the letter Ћ would win. Experts in writing and typography say that this letter is visually elegant, attractive and challenging in terms of calligraphy, and that it has a rhythm and a harmony to it. This letter, however, carries an additional value in terms of identity, since it is a clear trademark of the Serbian language, along with several other letters designed by Karadžić.

Just as the letter Ћ (equivalent in the Latin script is Ć) stands out among other letters, so also the Serbian Cyrillic stands out among other scripts. Philologist sometimes poetically point out that its importance to Serbia is like that of a root to a tree. As a sacred relic that was protected and passed on for centuries, the Cyrillic script today is not just a writing system – it is the voice of our ancestors and an enduring connection between epochs, land and language.

It is no wonder then that the construction of the first Serbian Cyrillic Museum in Rača near the eponymous monastery close to Bajina Bašta was financed by the government as a project of national importance.

According to Siniša Spasojević, creator and manager of the project, the project is based on the legacy of the scriptorium in the Rača Monastery (founded by King Milutin) during Ottoman rule, when numerous valuable medieval books were preserved. Also, during World War II, the monastery preserved the famous Miroslav Gospel, a manuscript with the finest example of the Serbian Cyrillic script.

The Museum will officially open by the end of the year and will be an important cultural centre dedicated to the preservation and promotion of one of the most important parts of Serbian cultural heritage.

More detailed information about the Cyrillic script, as well as numerous topics related to diplomacy, culture, and Serbia’s rich historical heritage, can be found in the Dipos Magazine.

2018

2018